COMMUNICATING IN THE THIRD SECTOR: PUBLIC SPEAKING AS AN ALLY

Marina Caymari, communications technician.

The Royal Spanish Academy defines public speaking as “the art of speaking eloquently and persuasively in public. It involves the use of specific techniques to communicate ideas in a clear, convincing and effective way, with the aim of influencing the audience”.

We often associate public speaking with politics or the business world, but rarely consider it a vital tool for the third sector. However, don’t we have projects to communicate and audiences to persuade, motivate and attract?

In a permanently connected society, where short and ephemeral messages prevail, the ability to connect with the public has become a real challenge for any entity.

In this article, we explore how we can improve our public speaking to strengthen communication with volunteers, beneficiaries and key stakeholders of a social project without talking about the dreaded crossed arms or powerful dramatic pauses.

The starting point

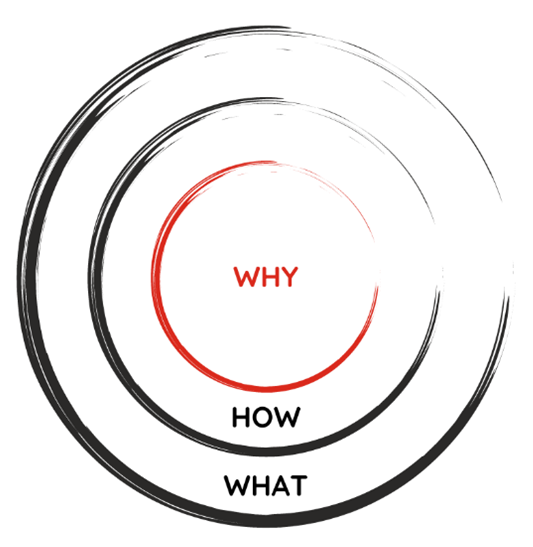

Simon Sinek, an expert in leadership and motivation, proposes in his Golden Circle theory that the most successful leaders and organizations inspire and connect best with their audience when they first communicate the“why” – their purpose or reason for being – before explaining the“how” – their process or values – and the“what” – their product or service. According to Sinek, “People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it. And what you do simply demonstrates what you believe.”

To speak from the “why” is to speak from authenticity. Here there are no nuances, specifications or comparisons, only a purpose, an objective, a goal, a belief.

To speak from the “why” is to speak from authenticity. Here there are no nuances, specifications or comparisons, only a purpose, an objective, a goal, a belief.

In the third sector, the Golden Circle theory takes on special relevanceWhen an organization communicates its “why” first, it is able to inspire and mobilize its stakeholders more effectively.

Keeping the balance

Connecting emotionally with the audience is crucial to create a deep and lasting bond. But why is this emotional connection so important?

Several studies claim that we remember better what affects us emotionally. One example is that of Cahill and McGaugh (1995), who investigated how emotions influence memory consolidation.

This study shows that events that affect us emotionally tend to be remembered with greater clarity and detail than neutral events. This is due to the activation of the brain amygdala, which plays a crucial role in the processing of emotions and the formation and storage of emotional memories.

As we can see, emotion allows us to connect in a deep and personal way, evoking feelings that can motivate and persuade. However, we must not forget the importance of rationality, which provides structure, logic and credibility, ensuring that the message is understood and consciously accepted.

According to Nancy Duarte, great communicators effortlessly combine emotion with rationality to create messages that resonate on both a personal and intellectual level, fostering a deeper connection and understanding with their audience (Duarte, 2019).

Thus, a speaker who properly combines both aspects can capture the audience’s attention, hold their interest and facilitate a change in their attitudes or behaviors. This duality is crucial for entities because it appeals to both the mind and the heart, which strengthens the message and its reception.

To whom and for what purpose

When communicating, it is as important to know what our purpose as an entity is as it is to know what our objective is with that communication, whether written or oral.

Are we trying to change behavior or raise awareness about something? Are we informing or convincing? Reflecting on the desired outcome of the communication will allow us to structure the message clearly and efficiently.

As Chip and Dan Heath (Heath, C., & Heath, D. 2007) said, we must ask ourselves: What do we want our audience to know? What do we want them to think, feel and do?

On the other hand, knowing who we are addressing is essential for our oratory to convince, influence and generate action.

On the other hand, knowing who we are addressing is essential for our oratory to convince, influence and generate action.

Wilcox, Cameron, and Xifra (2012, p.238) note that “knowledge of target audiences’ characteristics, such as beliefs, attitudes, concerns, and lifestyles, is an essential part of persuasion. They help the communicator craft tailored messages that are relevant, meet a need, and provide a logical development of actions.”

Non-verbal communication

The controversial nonverbal communication also occupies a space in the art of communicating, since, as Brooks, J. (2022) points out, body language, facial expressions and eye contact can reinforce or contradict the verbal message, thus affecting the reception and impact of the speech.

Much has been written and debated about best practices and common mistakes in public speaking – from crossing your arms or looking up, to standing with your legs spread as if you were in a John Wayne Western. However, we will not get into this debate.

In the end, the most important thing is to be aware of our non-verbal communication. Know that our gestures and expressions convey messages that may contradict (or not) our words. And, above all, do not overreact. The naturalness and authenticity of the speaker is what will allow us to generate credibility and connect with our audience.

For example, if a person who is very energetic, active, and mobile, is stuck behind a lectern on a stage, it is likely that he or she will start to make gestures that will sully his or her staging, such as jumping up and down (which may denote nervousness) or maintaining a bad posture.

For example, if a person who is very energetic, active, and mobile, is stuck behind a lectern on a stage, it is likely that he or she will start to make gestures that will sully his or her staging, such as jumping up and down (which may denote nervousness) or maintaining a bad posture.

Conversely, if someone is externalizing nerves through the hands, a handheld microphone might be more convenient than a headset microphone. It will keep the hands busy and in view.

On the other hand, if you tend to talk too fast and without pausing – which affects your breathing –there are two tricks that might help. First, squeezing the toes would help the tension move downward and allow the diaphragm to open up again. And secondly, if the communicative style is fast-paced, you can always add elements such as videos or audience exercises to break up the speech, allow you to catch your breath and pause the presentation.

There are many exercises and tips that can help improve nonverbal communication. However, the first step is to know yourself and analyze how you act when you speak. To do this, receive feedback from colleagues and, why not, recording yourself during practice can be essential.

In conclusion, internalizing and communicating the “why” of your entity; maintaining a balance between reason and emotion; being clear about what you are communicating for and to whom you are communicating; and knowing yourself as a speaker and relying on your qualities, will allow you, as a communicator, to be at the service of the message and make your communication effective and efficient.

References:

Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) (n.d.). Oratory. In Diccionario de la lengua española ( 23rd ed.).

Sinek, S. (2009). Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. Retrieved from https://startwithwhy.com/.

Cahill, L., & McGaugh, J. L. (1995). A novel demonstration of enhanced memory associated with emotional arousal. Nature, 371(6499)

Duarte, N. (2019). “DataStory: Explain Data and Inspire Action Through Story”. Hoboken: Wiley.

Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2007). “Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die”. New York: Random House.

Wilcox, D. L., Cameron, G. T., & Xifra, J. (2012). Public relations. Strategies and tactics (10th ed.). Pearson Education.

Brooks, J. (2022). “The Power of Nonverbal Communication: How to Use Body Language to Persuade and Influence.” New York: HarperCollins.