PEOPLE’S LEVEL OF EDUCATION: A DETERMINANT OF HEALTH AND LIFE EXPECTANCY?

The academic education a person obtains can define his or her life conditions, which is why reducing early school dropout rates can be a key factor in society’s life expectancy.

Lali Bueno, Zing Program Training Technician; and Verónica González, Zing Program Project Manager.

Reducing early school leaving (ESL), understood as the fact that students do not obtain any academic qualification beyond lower secondary school, is one of the main challenges at present, since it guarantees a higher level of education for society and, consequently, directly conditions the opportunities and future of young people in the territory.

The European Union set the objective of reducing the rate of AEP by 9% by the year 2030. According to data extracted from a report by the Bofill Foundation (Curran, Montes, 2022), in Spain only four autonomous communities meet the European target and Catalonia remains above the Spanish average with 14%, still far from the target.

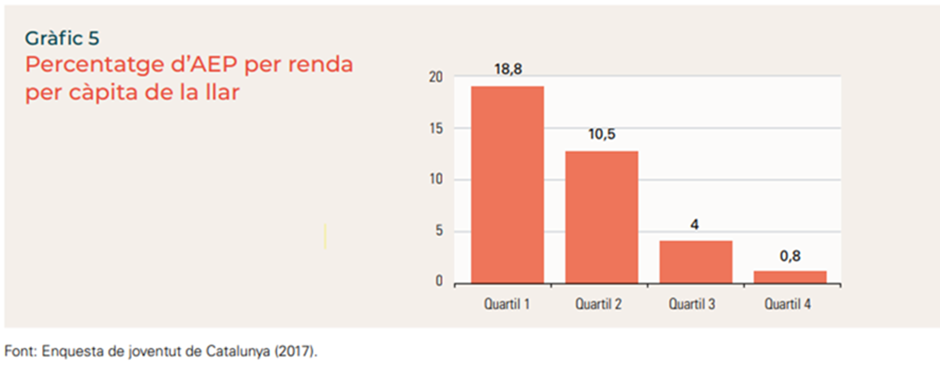

This challenge is even more alarming in the most vulnerable contexts. The data show that young people who have parents with lower levels of education and who live in low-income households drop out more; in other words, dropouts are more prevalent in the most disadvantaged households. This data, in turn, is related to their expectations for the future and their possibility of social mobility.

The Globalization, Education and Social Policies (GEPS) research group of the Department of Sociology of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona ratifies this reality in a recent report (Jover, Manzano, 2024), stating that the AEP has a clear impact on the reduction of opportunities for the people who live it and on their vital development, directly affecting important aspects such as the unemployment rate, employability in less qualified segments, difficulties in paying for housing, worse living conditions, worse general state of health and worse subjective wellbeing. These indicators, in turn, result in lower life expectancy, which is the focus of this article.

Early school dropout is more prevalent in more disadvantaged households and impacts on their life development

Relating early school dropout and the level of education attained to the socioeconomic situation of those who experience it is a decisive task in order to be able to take a social view of this reality. This view, at the same time, shows that the academic training a person achieves can be a conditioning factor in his or her life expectancy.

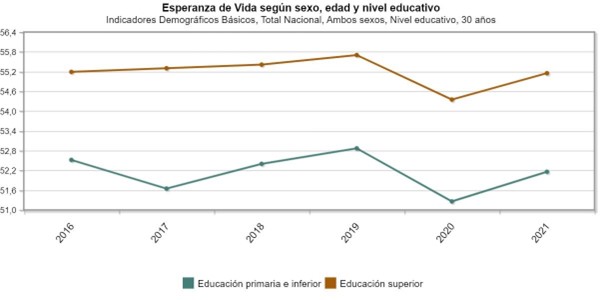

And this is indicated by the data extracted from the INE which, in comparison, show that life expectancy maintains a higher trend in people who have completed higher education than in those who have not. And, correlating both scenarios mentioned, life expectancy remains higher in households with a higher income, understanding that the data show that people who live in an environment with more economic resources (quartile 4) drop out at less than 1%, while those in the most precarious economic situation drop out at almost 20%.

How does educational level impact vital conditions, subjective well-being and life expectancy? We go deeper with data

Educational level and living conditions

It is evident that education plays a fundamental role in improving people’s living conditions and economic well-being. This idea is also in line with the human capital theory of economist Gary S. Becker, set out in his 1964 book ‘Human Capital’. This theory holds that investment in education provides positive returns, such as a higher probability of participation in the labor market, stability in employability and wage improvements. This scenario encourages people with a higher level of education to have more resources and knowledge to access health services, adopt healthy lifestyle habits and make informed decisions that have a positive impact on their health.

At the same time, educational inequalities have long-lasting effects from childhood. Children who grow up in disadvantaged environments are more likely to do less well in school and, as adults, earn lower incomes and experience more difficulties in providing good care for their own children, thus perpetuating the cycle of poverty and early school leaving. These adverse initial conditions significantly affect their future development and opportunities, as highlighted in the World Health Organization’s ‘Closing the Gap in a Generation’ report (2008).

Educational level and well-being

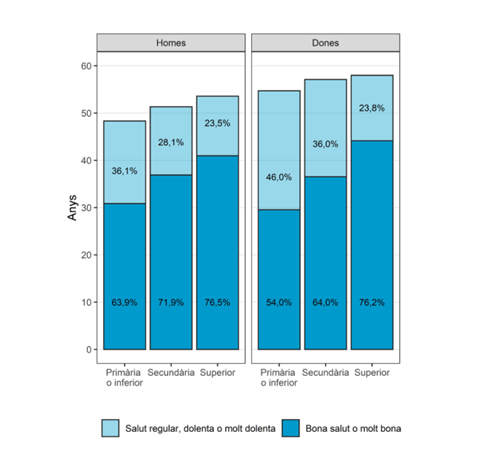

Self-perceived health is also a key indicator of overall health status. People with lower levels of education tend to perceive their health as worse compared to those with more education. According to data collected in the study ‘Perceived health and educational level in Spain’ (Aguilar, Carrera, Rabanaque, 2015), the least educated group in Spain shows a high percentage of poor self-perceived health. This phenomenon, known as the social gradient of health, indicates that the lower the socioeconomic level, the worse the perceived and actual health status, as can be seen in the following graph.

This phenomenon is even worse if we look at women: those with lower levels of education only enjoy good health for a little more than half of their lives, from the age of 30 onwards, while those with higher education do so for three quarters of the time. In other words, women live longer, but in poorer health.

Can a higher level of education make you live longer?

Thus, we see that the relationship between education and life expectancy is clear and strong, since education has a notable impact on mortality and health.

This is also reinforced by the study conducted by the Center for Demographic Studies (Blanes, Trias-Llimós, 2021): people with a lower level of education have a lower life expectancy. This analysis, carried out between 2017 and 2019, shows that in Spain men with higher education live 5 years longer than those with primary or lower education, while the difference in women is just over 3 years. These data show how education can act as a social elevator, improving not only economic conditions but also longevity.

In Catalonia, inequalities in life expectancy between neighborhoods are even more significant. If we focus on Barcelona, according to data from the City Council, the residents of Pedralbes have a life expectancy nine years higher than those of Vallbona. These differences reflect the economic and educational inequalities that coincide with life expectancy between the different areas. People in neighborhoods with higher income and education tend to have better health habits, less exposure to risks and better access to health services, factors that contribute to a longer and healthier life.

Prevention of ASP is a crucial issue for all actors in society, including in terms of health.

In conclusion, the relationship between educational level and health, as well as life expectancy, is evident and even more so in disadvantaged socioeconomic situations. In this sense, as we argued at the beginning, reducing early school leaving is therefore an irrefutable pending task that requires the collaboration of the whole of society. The different social agents have to work in a network to provide a response both in the educational field and in the sector of social entities, both of which must be accompanied by public policies to address the issue in a structural manner.

While educational centers have as a milestone to provide the necessary academic support to students in vulnerable situations, at the community level, social entities and companies can also contribute through projects to improve the opportunities of young people in these contexts. The objective then is to accompany public policies to ensure not only equal access to educational resources but also to work on their continuity.

How can this problem be addressed?

Employability programs such as the ZING program are fundamental to offer support to young people in vulnerable situations, improving their educational opportunities and, by extension, their health and quality of life. Not only by offering equal access to studies, but also by offering constant accompaniment to ensure that the continuity of studies is as guaranteed as possible. In this sense, ZING exemplifies this by offering young people in vulnerable situations various services such as vocational guidance, scholarship programs for access to studies, accompaniment and mentoring services during their itinerary and job orientation. Therefore, ZING not only seeks to reduce the AEP, but also to ensure the improvement of young people’s future prospects, as well as their quality of life.

The situation calls for understanding education as a social elevator that offers educational and professional opportunities that increase the well-being of individuals and their health. With collective and coordinated work, we can try to ensure a fairer and healthier future for everyone, reducing inequalities and promoting a more equitable and healthy society.

Sources consulted:

Aguilar Palacio, I. Carrera Las Fuentes, P., Rabanaque, M.J. (2015). Perceived health and educational level in Spain: trends by autonomous community and sex (2001-2012). Gaceta Sanitaria. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0213911114002015?via%3Dihub

Blanes, A., Trias-Llimós, S. (2021). Viure menys anys i en pitjor salut: el peatge de la població amb menor nivell educatiu a Espanya. Centre d’estudis demogràfics. https://www.ced.cat/PD/PerspectivesDemografiques_024_CAT.pdf

CSDH (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241563703

Curran, M., Montes, A. (2022). L’abandonament escolar prematur a Catalunya. https://fundaciobofill.cat/uploads/docs/y/f/d/isl-abandonament_091122_curran_2.pdf

Jover, A., Manzano, M. (2024). Project of evaluation and improvement of indicators of the Zing Program.