A HOLISTIC ASSESSMENT OF MENTORING

Alba López Martínez and Víctor González Núñez, Mentoring Technician and Coordinator of the accompaniment axis.

Socio-educational mentoring has emerged as a powerful tool, but to date its impact has been little evaluated and contrasted by the different projects that carry it out.

As we argued in the first Congress of the Ibero-American Mentoring Network (RIME), evaluation has a fundamental role in order to analyze the real impact and not rely on conclusions and intuitions that are not very empirical (González Núñez, 2023).[1]. Also during the congress, we were able to reflect on the importance of evaluating the processes not only to measure the impact, but also to add value and thus offer the participants an improved version each time (López Martínez, 2023).[2].

On the other hand, Rhodes also emphasizes the importance of delving deeper into the effects of mentoring in the social domain, an area that has not been addressed in detail and that constitutes a knowledge gap. More research and broad, interdisciplinary theoretical frameworks are needed to guide the actions of organizations implementing social mentoring programs (Rhodes et al., 2006).

That is why from the Zing Mentoring project, we have created an instrument that allows us to analyze and evaluate the impact that mentoring relationships have on both young people and mentors. This tool provides us with the IQA (Índex de Qualitat dels Acompanyaments), a quantitative result obtained through the sum and weighting of several indicators derived from evaluations made throughout the course to the mentoring couple.

Composite indicators, a common evaluative practice in major international governance bodies

The aggregation of several variables in order to obtain one is known as a composite indicator, and is considered a good evaluative practice when seeking to obtain a simplified representation that summarizes a multidimensional concept in a unidimensional one. [3]

This data collection is framed within the quantitative evaluation typology, which shows us in numbers and graphs what is observable, connecting the empirical observation and the mathematical expression derived from having asked at all times specific and quantifiable questions, all framed within the rationalist paradigm.

One of the best known examples of the use of composite indicators is the MPI.[4] (Multidimensional Poverty Index), by the United Nations, or the GDI.[5] (Gender Inequality Index), by EIGE, the European Institute for Gender Equality. In the case of the MPI, there are 9 aggregated indicators, while in the GDI there are up to 31.

We believe it is pertinent to make this clarification, as well as to specify that in intervention projects with people, as is the case of socio-educational mentoring projects, it is essential to take into account and give a high value to qualitative research. As Cotán (2016) states.[6], this typology has “great importance due to the subjective experience of individuals in the construction of the social world, understanding reality as multiple and divergent”. Qualitative research seeks, therefore, the deepest possible understanding, while quantitative research seeks accuracy.

Having made this brief note, and understanding the vital importance that depth and, therefore, qualitative evaluations have in interventions of this type, we can go on to explain and understand the Mentoring Quality Index, the compilation of quantitative data that will allow us to have a fairly accurate picture of what has happened within a mentoring relationship.

Understanding first of all that we are simplifying the data we have, and before seeing what potential this has, it is key to keep in mind that this aggregation of data must be conceptually supported on the basis of an underlying model.

Once all these elements linked to the model have been analyzed, we have a clear view of the information that we wish to extract and measure in order to verify that the determined objectives are achieved and to what degree they are achieved. At this point we design the corresponding indicators for such verification and choose those we consider to be most relevant for such analysis.

In the case of the Mentoring project of the ZING Program, the technical team decided that there are 25 key indicators that allow us to get closer to knowing what has been the quality of the accompaniment within the framework of a relationship. Despite being able to prioritize them, we consider that the aggregate of these 25 variables will contribute to the formulation and analysis of future interventions, as well as to their evaluation and communication.

Even so, these types of composite indicators facilitate:

a) Interpretation of the scenarios by the decision-makers (the coordinators or designers of these interventions).

b) its justification to current or future funders (public or private) by creating an accessible narrative that helps us explain what we do.

c) Comparison between different projects (with the aim of being able to transfer what good practices one project does or another does if we establish causal inferences).

d) The evolution of the same project from year to year in order to determine what elements of improvement may exist, and finally to be able to establish parameters that make it possible to foresee the best quality of an accompaniment according to certain actions that are developed within it.

This tool also has its risks, which can be grouped into two:

- Lack of methodological care in the compilation of data.

- Lack of information on them.

The first point leads us to talk about the sources through which we obtain the data, where we consider that there is room for improvement. These sources are four:

- Objective aspects, such as the number of meetings, the number of Quarterly Evaluation Meetings or the attendance to the Group Cultural Activities.

- The youth’s evaluation of the impact that mentoring has had on him/her.

- The mentor’s evaluation of the impact the mentoring has had on him/herself and on the mentee.

- The benchmarking technique’s evaluation of the impact that mentoring has had on the partners.

Although it is a common practice in the evaluation of socio-educational mentoring projects, as well as in the social field in general, self-assessment is a tool that has certain limitations, mainly the bias that stakeholders (in this case the mentored person and the mentor) may have when assessing the impact that the accompaniment has had on them. In this sense, from the Nous Cims Foundation we are developing the Competency Assessment Tool, together with the Social Mentoring Coordinator, the consulting firm specializing in employability skills EySkills and six social mentoring entities. The EAC must allow us to have observable behaviors that the maximum number of possible agents (educational tutor, mentor, mentoring technician, family, young person) can evaluate, and thus leave the least possible margin for subjective interpretation of the data; something that is of particular relevance when we want to determine the impact that the action has had on the development of transversal competencies.

The second point is the importance of the validity of the data. At the individual level of each accompaniment, the fact that the young person and mentor have usually answered the follow-up questionnaires, as well as the end-of-course evaluation, will be essential to be able to determine that the final data are relevant and pertinent. While at a general level, having a high number of responses, especially in the final evaluation, will allow us to validate the data that may come out, and to draw conclusions and analysis of them without generalizations or misinterpretations.

The tool: IQA

The IQA arose from the need to make a more quantitative assessment of mentoring relationships, and so during the 21/22 academic year, the team created the first version of the tool. Currently, we continue to make annual improvements that allow us to obtain live and dynamic results, which favor technical follow-up and provide more information on the evolution of these relationships so that we can also make improvements.

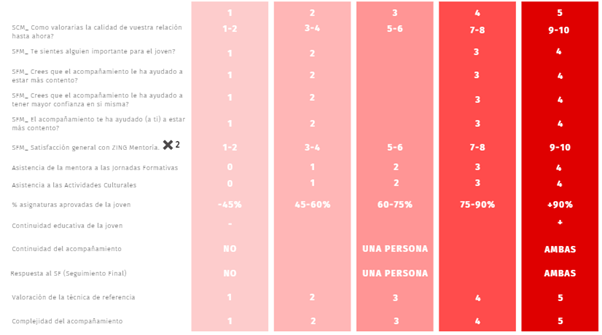

As we can see in Figure 1, the tool consists of 25 indicators extracted from various evaluations carried out throughout the course, which can be divided into five blocks.

The first block consists of the “hard” data, where the scores are drawn from several factors; the closure, where the time the relationship has been alive, the number of meetings they have held during the course, the cultural activities they have attended and the number of quarterly meetings that have been held with the reference technique are evaluated.

The second block extracts the scores of the evaluations carried out by the young person during various moments of the course; monthly continuous evaluation, the final evaluation of the course, the notes extracted from the competency observation grid and the academic results. On the other hand, we have the third block, which is nourished by the scores made by the mentor during the whole course in the following moments: continuous evaluation every time he/she meets the mentor, the final evaluation and the trainings.

The fourth and fifth blocks are aimed at obtaining more qualitative information on the relationship, extracted from the perception of both the reference technician and the educators or educational agents. This note, among others, has been and is a subject of debate in the team, as well as other aspects such as whether the moment of initiation of the relationship should be a factor to be taken into account or whether the couples who repeat should have different weightings.

For this reason, work is already underway on the third update of the tool, where all these issues, along with other improvements, must be taken into account and discussed, such as the impact of mentoring on strengthening social cohesion and how to measure it.

Challenges and partial conclusions on the IQA

In the current state of primary development of the index, and in addition to the constant revision of the indicators that are part of it, there are two main challenges to further refine and improve the reliability of the tool when concluding aspects:

- The first is the use we can make of the extracted data, and here we can refer to two aspects: on the one hand, the possibility of having a live updated IQA during the course of the mentoring relationship could be a tool that very quickly and visibly provides information to the technical team doing the follow-up on what is happening (or not happening) within a mentoring relationship. This point could mean an important advance in the qualitative intervention of the techniques, which would hypothetically lead to a higher quality of the accompaniments; as well as to a more efficient management of the available resources by being able to have a very agile snapshot of each relationship, not only once the mentoring ends in July. And, on the other hand, the cross-referencing of the aggregate data in the IQA with other variables such as age, gender, type of studies, etc. to draw conclusions about the profile of young people or mentors for whom this type of intervention has a greater impact.

- The second is the establishment of control groups, in the broadest sense of the concept, to compare the final data with other relevant data. This could be derived from the comparison between different academic courses within the same project or the comparison with other mentoring projects that can be used to detect good practices and thus transfer valuable knowledge.

In conclusion, we consider the Mentoring Quality Index to be a valuable tool for evaluating the overall development of a mentoring project within the framework of an academic year. It is also a tool with potential to analyze at a micro level what has happened in a mentoring relationship, and to draw conclusions about certain patterns of good behavior or profiles with potential for greater impact.

We also believe that the possible development of the IQA requires the validation of its contents by umbrella entities such as the Social Mentoring Coordinator, which will allow us to assess its possible transfer and adaptation to other projects.

Finally, despite the promising conclusions that an index such as the IQA can offer to the projects that implement it, we stress the need to deepen and give value to qualitative evaluation, to go into depth to understand the impact on the people involved in a mentoring relationship.

References

[1] González Núñez, V. (2023). Evaluating its impact, one of the keys to the future of socio-educational mentoring. RIME, 1st Iberoamerican Congress for Quality Education: Mentoring and Competency Development. Barcelona. https://www.nouscims.com/evaluar-su-impacto-una-de-las-claves-del-futuro-de-la-mentoria-socioeducativa/

[2] López Martínez, A. (2023). The experience of the ZING mentoring program in the acquisition of educational and labor competencies. RIME, 1st Iberoamerican Congress for quality education: Mentoring and Competency Development. Barcelona. https://www.nouscims.com/la-experiencia-del-programa-de-mentoria-zing-en-la-adquisicion-de-competencias-educativas-y-laborales/

[3] Schuschny, H, and Soto, A (2009). Methodological guide for the design of composite indicators of sustainable development. ECLAC-UN. Santiago de Chile. https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a627f68b-9902-4fa2-a516-912a903ecf22/content

[4] Action Against Hunger (2022). Poverty index, what is it and how is it calculated?. https://www.accioncontraelhambre.org/es/indice-pobreza-que-es

[5] Statistical Institute of Catalonia (2022). Gender Equality Index. https://www.idescat.cat/pub/?id=iig&lang=es&m=m

[6] Cotán Fernández, A. (2016). The meaning of qualitative research. Isabel University. Burgos. https://www.ceuandalucia.es/escuelaabierta/pdf/articulos_ea19/EA19-sentido.pdf